The household, an economic entity along with the government and enterprises

From consumption tax increases to COVID-19 responses, government policies are intertwined with activities in our daily lives. Changes in economic activities occur not only due to taxation systems but also as a result of social framework shifts and legal revisions. These changes can have a significant impact on our individual lives. Professor Yoko Niimi of the Faculty of Policy Studies, Doshisha University addresses these issues through the perspective of “household economics,” her field of specialization within the microeconomics domain. Her empirical research thus focuses on the household.

“In economics, the household is one of the primary economic entities, alongside the government and enterprises. Specifically, a household performs economic activities in its daily lives, working and earning wages and buying goods in its role as a consumer. An accurate understanding of the household is thus key to designing and implementing appropriate policies for social issues, including poverty and inequality.” Professor Niimi emphasizes that it is imperative that government policies help improve people’s wellbeing. “Under any government policy, there are people who benefit and those who do not—some may even suffer as a result. Although it is not easy to create even-handed policies, we must ascertain how each specific policy impacts individuals and provide necessary measures for those who are affected negatively. This is why placing a focus on the household has enormous significance.”

Professor Niimi’s research approach is closely linked to her extensive global experiences. She has worked at the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank, organizations that assist developing nations. Her research has spanned many countries, including Bhutan and Vietnam. “At first, I used to analyze poverty and inequality from a relatively macroeconomic viewpoint. For example, I examined the impact of such measures as free-trade policies and regional trade agreements on poverty and inequality. However, when I personally observed the situation in developing regions, I felt the need to take a closer look at the lives of people, to see things from a ‘micro’ perspective.”

Empirical analysis of a support system for working caregivers

While Professor Niimi continued her studies of emerging Asian nations, recently she also published papers about Japan. One of them is titled “Juggling Paid Work and Elderly Care Provision in Japan: Does a Flexible Work Environment Help Family Caregivers Cope?” This is an empirical study on the relationship between family caregivers’ employment and the caregiver-leave system, which allows a 93-day leave from work, based on the law, The Child Care and Family Care Leave Act. Professor Niimi served as a member of the “Research group on employment and social safety net during the childcare and/or long-term care period,” a group formed within the Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training, an independent administrative institution under the jurisdiction of the Japan Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW). In the Group, Professor Niimi was responsible for the “long-term care” theme. “Unlike childcare, any person can suddenly become a family caregiver with no definite end in sight. The challenges that the caregiver faces are also diverse and depend on the care recipient’s illness, current disability status and possible trajectory, and family composition and environment, among others. To establish a system that enables family members to continue working even as they take on the burdens of long-term care, it is important for each family to coordinate closely with home helpers, care facilities, hospitals, and more. The current caregiver-leave system is not designed to allow workers to take a continuous leave to provide long-term care; instead, it provides some off-work time to enable the family caregiver to set up a system involving the aforementioned actors. The main aim of this caregiver-leave system is thus to help family caregivers maintain their jobs despite their caregiving responsibilities.”

A major survey was conducted among workers who experienced caregiving after the long-term care insurance program was introduced in Japan in 2000; the number of persons surveyed was around 4,000 persons. Professor Niimi was involved in the creation of the survey questionnaire, and detailed data were collected. The data included information on family composition at the time when the care recipient became in need of care, whether the caregiver availed himself/herself of flexible work arrangements offered at his/her workplace, and any changes in the caregiver’s employment status since the occurrence of long-term care needs within the family. Professor Niimi’s results suggest that the caregiver-leave system helps prevent family caregivers from having to leave their jobs

( Figure. 1).

Source: Niimi, Y. (2021)”Juggling Paid Work and Elderly Care Provision in Japan:

Does a Flexible Work Environment Help Family Caregivers Cope?”

Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, 62, 101171.

Her research has sparked keen interest in Japan and abroad. Invitations have come from academic societies to attend conferences in Singapore and Taiwan, and researchers in France have requested Professor Niimi to join an international research project on long-term care. “Although Japan is the country with the most aged population, Europe and other regions are also facing aging-related issues. Population aging is also progressing in Asia, not only in China but signs of aging can also be seen in some other emerging nations. While multifaceted research is being performed worldwide on caregiving-related issues, strong interest has been shown in Japan’s unique caregiver-leave system. Certainly, researchers and policymakers worldwide are looking to Japan to understand how she responds as the most aged country in the world.”

Research on the effects of marriage on the wealth accumulation of Japanese women

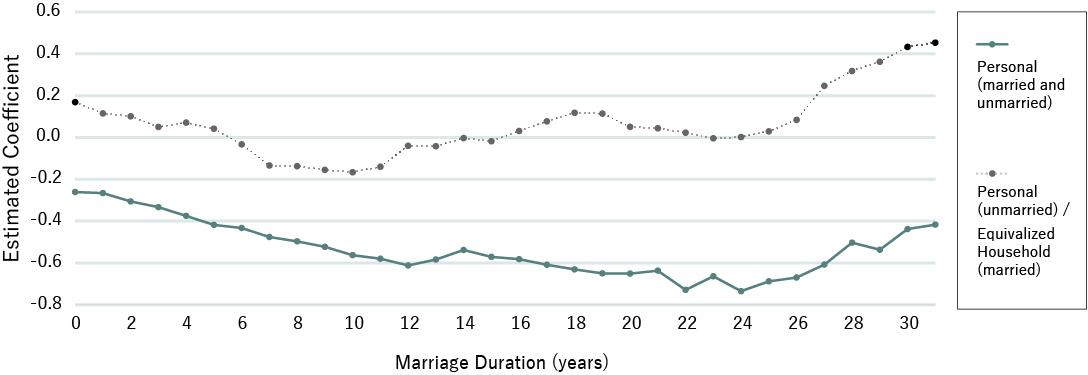

Analyses of household behavior can help highlight a broad range of social issues. In addition to poverty and inequality, Professor Niimi has also focused on gender equality. One of her recent research papers is titled “Are Married Women Really Wealthier Than Unmarried Women? Evidence From Japan.” In this study, Professor Niimi analyzed the relationship between marriage and the wealth accumulation of Japanese women using data collected for more than two decades. Unlike income data, wealth data tend to be collected only at the household level. Thus, empirical research on the distribution of wealth within a household has been very limited so far not only in Japan but also in other parts of the world. While the gender gap has been widely studied in the areas of education and employment, Professor Niimi has shed new light on its existence in asset formation. She found that marriage does not necessarily have a positive impact on the wealth accumulation of Japanese married women if we focus on their personal wealth (Figure. 2).

Source: Niimi, Y. (2022) “Are Married Women Really Wealthier Than Unmarried Women? Evidence From Japan,”

Demography, 59(2), pp. 461-483.

“Looking at the case of household wealth as a whole by ignoring the ownership of assets, marriage generally has a positive impact on women’s wealth accumulation. In contrast, assets held in the woman’s own name are found to decline after she marries. This can be explained largely by the fact that married women’s personal income tends to decline as they leave their jobs or reduce their working hours because of childbirth and childcare responsibilities. Also, unlike in other countries, asset transfers between spouses are subject to a gift tax in Japan. Thus, when the woman does not work and/or when she has few or no assets in her own name, it is difficult for her to purchase a home jointly with her husband in Japan. This is likely to have a negative impact on women’s wealth accumulation. All of this can increase a wife’s financial dependency on her husband and could weaken her economic standing when an unexpected separation occurs. It is therefore important that there exists a system that encourages women to accumulate assets that are registered in their own names.” Professor Niimi’s keen insight and detailed analysis of personal asset formation has shed light on the difficult circumstances faced by Japanese women.

Professor Niimi says the source of her motivation for empirical research is in the fact that she can provide objective evidence and proof for why a particular phenomenon exists using various estimation methods and data. “At first you might have intuitions and unformed assumptions. Yet, as you confront and analyze data, you start observing some trends. In many cases, you make interesting discoveries, including results that defy your initial thoughts and expectations.”

Our world requires people like Professor Niimi, who merge two fine and essential qualities. First, she has the sensibilities of a superior researcher who can analyze data logically with a calm and deliberate perspective. Second, Professor Niimi possesses human warmth and feelings for those who are disadvantaged, as she continuously strives for the realization of a society where no one is left behind.