Research News:Can Phrases Like ‘Isn’t it?’ or ‘Right?’ Compromise Classroom Learning? New Study Answers

May 31, 2023

A researcher in Japan noted that the use of interrogative tags such as ‘isn’t it?’ and ‘right?’ by the teachers can limit student involvement and learning.

Teachers often repeat a student’s answer followed by an interrogative tag such as ‘you know’, ‘isn’t it’, and ‘right?’, to ensure that students feel like a collective during a classroom discussion. A new study from Japan explored the use of ‘ne’, a term with similar meaning as these interrogative tags, that are commonly used by Japanese teachers. The researchers found that using this strategy can often limit the response of some students and prevent follow-up questions.

Classroom education, in an ideal sense, must engage all students in a constructive discussion with the teacher, making it the latter’s responsibility to utilize different inclusive strategies. To bring the attention of distracted students back to the classroom discussion, teachers often have to use different methods to remind them that they are an equal and important part of this shared activity. This task can be tricky since most teachers attend to multiple students in a classroom. What strategies do teachers use to draw the attention of all the students to the common thread of a classroom discussion?

In a study that was recently published in Classroom Discourse, Dr. Mika Ishino of Doshisha University explored this question by analyzing the video recordings of classroom interactions between teachers and students in Japan. Dr. Ishino specifically examined how teachers employed the epistemic stance marker ‘ne’ during the classroom discussions, to make the interaction more inclusive with all the students. An epistemic stance marker is a word that modifies the tone of a sentence, to increase the interpersonal interaction between the speaker and the listener. “‘ne’ is roughly equivalent to English interrogative tags ‘you know’, ‘isn’t it’, and ‘right?’. It mainly marks the sharedness of the referent information between the speaker and the hearer,” explains Professor Ishino.

The study found that the epistemic stance marker ‘ne’ is commonly used in the third-turn during teacher-student interactions. In the first turn, the teacher asks a question to the class as a whole. In the second turn, one student usually answers the question. For the third-turn, the teacher then repeats the answer and adds ‘ne’ to open the interaction and include the rest of the students in this exchange.

“When the teachers produced their third-turn repeat in response to an individual student’s reply, they marked the repeated item with the Japanese epistemic stance marker, ‘ne’ or ‘na’, and shifted their gaze from the respondent individual to other students or ‘public space’ such as the blackboard”, Dr. Ishino observes. She further adds, “In doing so, the teachers treated the rest of the students as the party who also had access to the questioning item in the same manner as the respondent student.”

By using the third-turn repeat ‘ne’, teachers modify the nature of the interaction such that all students in the class, including the distracted, are given equal status in the discussion. Once this happens, the teacher moves on to the next question. However, Dr. Ishino found that this practice can have a negative impact on student involvement and learning. When the teachers use the third-turn repeat as a consistent strategy without checking if all the students are in sync, they potentially curtail the chance of any follow-up questions that the students can ask. “If there is a possibility that some students were not on the same page with the respondent student or did not know the answer to the questioning items, the inclusive third-turn repeat is designed to limit the students’ responses to a silent agreement,” Dr. Ishino concludes.

The study reveals that in an interaction with multiple students, it is crucial for teachers to ensure that no student is more privileged than others. Furthermore, the use of third-term repeats like ‘ne’ may be a helpful way to encourage inclusive learnings during classroom discussions. However, it can have serious negative consequences on student involvement and learning in the long term.

Impact of Third-Turn Repeat on Student Learning

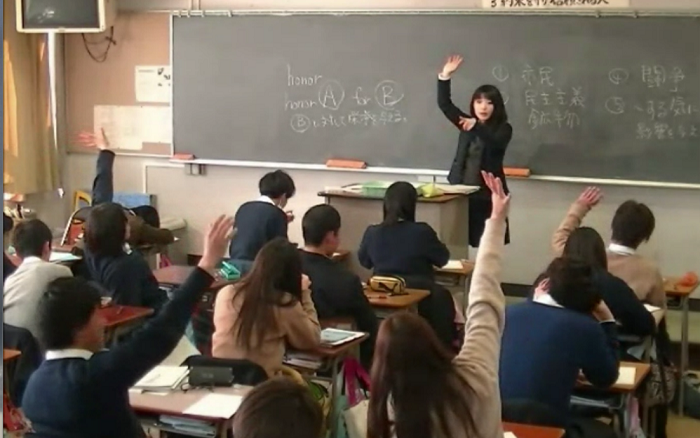

While teachers use the third-turn repeat strategy to encourage student inclusion, it might silence curiosity.

Image courtesy: Mika Ishino

Usage restrictions: No restrictions Image license: Original content

Reference

| Title of original paper | Inclusive Third-Turn Repeats: Managing or Constraining Students’ Epistemic Status? |

| Journal | Classroom Discourse |

| DOI | 10.1080/19463014.2023.2190033 |

Funding information

The Japan Society supported this work for the Promotion of Science under Grant number:19K13305.

Profile

Dr. Mika Ishino is an associate professor in the Faculty of Global and Regional Studies, Department of Global and Regional Studies at Doshisha University. Her academic interests include applied linguistics, language teacher education, and conversation analysis. She has previously worked at public high schools in Japan as an English teacher. Her research interest mainly lies in how teachers accomplish the pedagogical goals in their classroom institutional settings. She has also been the recipient of the ‘Best Paper Award’ by the Japan Society of Educational Sociology.

Mika Ishino

Associate Professor , Faculty of Global and Regional Studies Department of Global and Regional Studies

Media contact

Organization for Research Initiatives & Development

Doshisha University

Kyotanabe, Kyoto 610-0394, JAPAN

CONTACT US